Central Bank Gold Agreements

On 19th May 2014, the European Central Bank and 20 other European central banks announced the signing of the fourth Central Bank Gold Agreement. This agreement, which applies as of 27 September 2014, will last for five years and the signatories have stated that they currently do not have any plans to sell significant amounts of gold. For further information, please click here.

Collectively, at the end of 2018, central banks held around 33,200 tonnes of gold, which is approximately one-fifth of all the gold ever mined. Moreover, these holdings are highly concentrated in the advanced economies of Western Europe and North America, a legacy of the days of the gold standard. This means that central banks have immense pricing power in the gold markets.

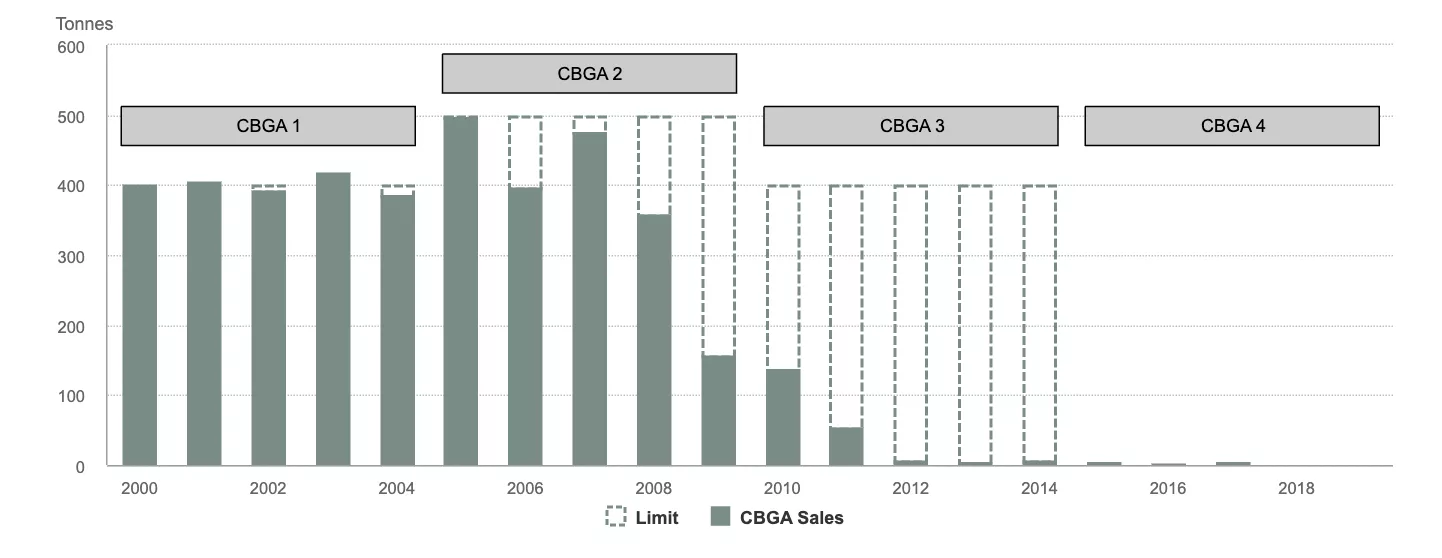

In recognition of this, major European central banks signed the Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) in 1999, limiting the amount of gold that signatories can collectively sell in any one year. There have since been three further agreements, in 2004, 2009 and 2014.

Central banks have a commitment to being stewards of stable markets, in particular where it involves their own investment behaviour. The sharp and abrupt swings in the gold price prior to the first CBGA show what a world without an agreement might look like. The agreements have provided the gold market with much needed transparency and a commitment from global central banks that they will not engage in uncoordinated large-scale gold sales.

The agreements have been beneficial to all aspects of the gold market from gold producers, fabricators, investors and consumers and in particular to heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC), several of whom are large exporters of gold. Central banks have also benefited from the agreements due to the enhanced stability they have brought to the gold market and to the market value of reserves.

In a sign of central banks’ positive sentiment towards gold, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced that its 20-year old Central Bank Gold Agreement would not be renewed when it expires in September 2019. The ECB said that it and the 21 other central banks that are signatories to the agreement: “confirm that gold remains an important element of global monetary reserves, as it continues to provide asset diversification benefits and none of them currently has plans to sell significant amounts of gold.” The ECB also noted that: “signatories have not sold significant amounts of gold for nearly a decade, and central banks and other official institutions in general have become net buyers of gold.

Central Bank Gold Agreements

The First Central Bank Gold Agreement

The first Central Bank Gold Agreement, also known as the Washington Agreement on Gold, was announced on 26th September 1999. It followed a period of increasing concern that uncoordinated central bank gold sales were destabilising the market, driving the gold price sharply down.

At the time, central banks held nearly a quarter of all the gold estimated to be above ground, equivalent to around 33,000 tonnes in September 1999, and had an enormously influential position in the gold markets.

The central banks of Western Europe in particular held—and still hold—substantial stocks of gold in their reserves. Those in the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, Switzerland and the UK, had already sold gold or announced their intent to do so. Others were taking advantage of rising demand for borrowed gold and increasing their use of lending, swaps and other derivative instruments. An increase in lending typically resulted in additional gold being sold, meaning that the trend was adding further supplies to the market.

In addition to the destabilising effect of these sales, market fears about central bank intentions were causing further falls in the price of gold. This was causing considerable pain for gold producing countries. Among these were a number of developing countries, including a significant number of those classified as HIPCs (Heavily Indebted Poor Countries).

In response to these concerns, 15 European central banks—those of the then 11 Eurozone countries and of Sweden, Switzerland and the UK, as well as the European Central Bank—drew up the first Central Bank Gold Agreement, ‘CBGA1’. The agreement was signed in Washington DC, during the 1999 annual meetings of the International Monetary Fund.

In it, they stated that gold would remain an important element of global monetary reserves, and agreed to limit their collective sales to 2,000 tonnes over the following five years, or around 400 tonnes a year.

They also announced that their lending and use of derivatives would not increase over the same five-year period. The signatory banks later stated that the total amount of their gold they had out on lease in September 1999 was 2,119.32 tonnes.

The signatory banks accounted for around 45 per cent of global gold reserves. In addition a number of other major holders—including the US, Japan, Australia, the IMF and the Bank for International Settlements—either informally associated themselves with the Agreement or announced at other times that they would not sell gold.

The announcement of the agreement came as a major surprise to the market. It prompted a sharp spike in the price over the following days, but it also removed much of the uncertainty surrounding the intentions of the official sector. Once the markets had adapted to it, a major element of instability had been effectively removed with the introduction of greater transparency.

Press release – joint statement on gold, 26th September 1999

The Second Central Bank Gold Agreement

On 8th March 2004, the signatory banks announced the second Central Bank Gold Agreement. Like the first agreement, ‘CBGA2’ covered a five-year period, in this case from 27th September 2004 to 26th September 2009.

The second agreement started by reaffirming the first clause in its predecessor: “Gold will remain an important element of global monetary reserves”.

While the rest of the agreement covered similar ground to the first, there were some important differences.

The UK signed the first agreement but not the second, having previously stated that it had no plans to sell gold. Greece, which had not been a member of the Eurozone in 1999, did not sign the first Agreement but signed the second. Slovenia became a signatory to the second Agreement in December 2006, shortly before adopting the euro as its currency. Cyprus and Malta also joined CBGA2 just after they joined the euro.

In CBGA2, the maximum amount of gold that the signatories could sell over the five years was 2,500 tonnes, with an annual ceiling of 500 tonnes; an increase over the previous agreement, which permitted annual sales of 400 tonnes, up to a maximum of 2,000 tonnes over five years.

CBGA2 also limited central banks from increasing their use of futures and gold leasing above pre-1999 levels of around 2,100 tonnes.

The Third Central Bank Gold Agreement

The third Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA3), which was signed in 2009, covered the gold sales of the Eurosystem central banks, as well as Sweden and Switzerland. Like the previous two agreements, CBGA3 covered a five-year period, in this case from 27th September 2009, when the second Agreement expired, to 26th September 2014.

CBGA3 reaffirmed that "gold remains an important element of global monetary reserves", as was stated in the two previous agreements. This agreement also included two important departures from those that came before it.

Firstly, the banks reduced the maximum amount of gold that they could collectively sell, capping annual sales at 400 tonnes, and total sales across the five-year period at 2,000 tonnes. This is 500 tonnes lower than the 2,500 tonnes ceiling for the previous five-year agreement, CBGA2. During the final two years of CBGA2, the signatories had significantly undersold their permitted annual ceiling, so the reduced total in CBGA3 did not come as a surprise to market participants.

IMF gold sales

The second significant difference in the new agreement recognised the fact that the International Monetary Fund intended to sell a proportion of its gold.

Following an internal report in 2007 that recommended it restructure its income models, the International Monetary Fund’s executive board approved the sale of 403.3 tonnes of gold in September 2009, around one-eighth of the institution’s total gold holdings.

The IMF conducted the first phase of these sales in off-market deals with other central banks, thereby leaving the stock of gold in the official sector unchanged. This included 200 tonnes sold to the Reserve Bank of India, 10 tonnes each to the central banks of Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, and 2 tonnes to the Mauritian central bank.

The IMF began phased on-market sales in February 2010 and sold 191.3 tonnes.

In CBGA1 and CBGA2, signatories undertook not to increase their activities in the derivatives and lending markets above the levels of September 1999, when the first CBGA was signed. The 2009 agreement included no similar commitment, although central bank activity in these fields has been very limited in recent years.

ECB Press release - Joint statement on gold, August 7th 2009

The Fourth Central Bank Gold Agreement

19 May 2014 - ECB and other central banks announce the fourth Central Bank Gold Agreement

The European Central Bank, the Nationale Bank van België/Banque Nationale de Belgique, the Deutsche Bundesbank, Eesti Pank, the Central Bank of Ireland, the Bank of Greece, the Banco de España, the Banque de France, the Banca d’Italia, the Central Bank of Cyprus, Latvijas Banka, the Banque centrale du Luxembourg, the Central Bank of Malta, De Nederlandsche Bank, the Oesterreichische Nationalbank, the Banco de Portugal, Banka Slovenije, Národná banka Slovenska, Suomen Pankki – Finlands Bank, Sveriges Riksbank and the Swiss National Bank today announce the fourth Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA).

In the interest of clarifying their intentions with respect to their gold holdings, the signatories of the fourth CBGA issue the following statement:

- Gold remains an important element of global monetary reserves;

- The signatories will continue to coordinate their gold transactions so as to avoid market disturbances;

- The signatories note that, currently, they do not have any plans to sell significant amounts of gold;

- This agreement, which applies as of 27 September 2014, following the expiry of the current agreement, will be reviewed after five years.

The ECB and gold

The European Central Bank (ECB) was established in 1998 to help manage the economic and monetary integration of the European Union. Before the official launch of the European single currency on 1st January 1999, the central banks of the prospective euro area transferred foreign reserve assets to the new institution.

In one of its first pronouncements, the governing council of the ECB decided that gold should be part of those transfers.

Of the initial transfer of assets, which amounted to nearly €40 billion,the ECB agreed that 15 per cent should be in gold, a clear demonstration of the fact that European policymakers continued to believe that gold strengthened the balance sheet of a central bank and enhanced public confidence.

The ECB indicated clearly that these transfers of gold would not affect the total consolidated gold holdings of the Eurozone. The remaining 85 per cent was transferred in foreign currency assets, but there was no implication that the ratio would remain the same.

Despite a number of sales, gold’s share of the ECB’s total reserves has grown considerably since then, due to the sharp increase in the gold price. As at July 2016, the ECB had 28 per cent of its reserves in gold.

Recent levels of CBGA sales

Gold is an important component of central bank reserves because of its safety, liquidity and return characteristics – the three key investment objectives for central banks. As such, they are significant holders of gold, accounting for around a fifth of all the gold that has been mined throughout history. To help understand this sector of the gold market, we publish gold reserve data – compiled using IMF IFS statistics – which tracks central banks’ (and other official institutions, where appropriate) reported purchases and sales along with gold as a percentage of their international reserves.

For more information see our Gold Demand Trends report.

European Gold Sales within Central Bank Gold Agreements

Sources: European Central Bank, International Monetary Fund, World Gold Council

Note: Data to end-June 2017