Gold has been on an upward trajectory since June and the price is now at record levels in many currencies. Does this mean we are moving into a new bull market for gold?

To answer that question, we looked back in time, assessing how gold has performed over the past century and the key characteristics of gold bull markets.

Our research showed that gold bull markets are most likely to develop during global currency crises, bond bull markets, commodity bull markets or a combination of all three.

1. Global Currency Crises

The Great Depression of 1929 and the collapse of the Bretton Woods System in 1971 provoked dramatic currency crises. These, in turn, triggered prolonged gold bull markets.

The revaluation of the gold price in 1934

Looking first at the Great Depression; this began when Wall Street crashed in 1929, plunging the American economy into a vicious circle of deflation and stagnation. In January 1934, the US Congress passed the Gold Reserve Act to try and stimulate the economy. This gave President Roosevelt the right to devalue the dollar and he swiftly announced a re-evaluation, adjusting the price of one ounce of gold from US$20.67 dollars to US$35, an increase of more than 70%.

The “Nixon shock” of 1971

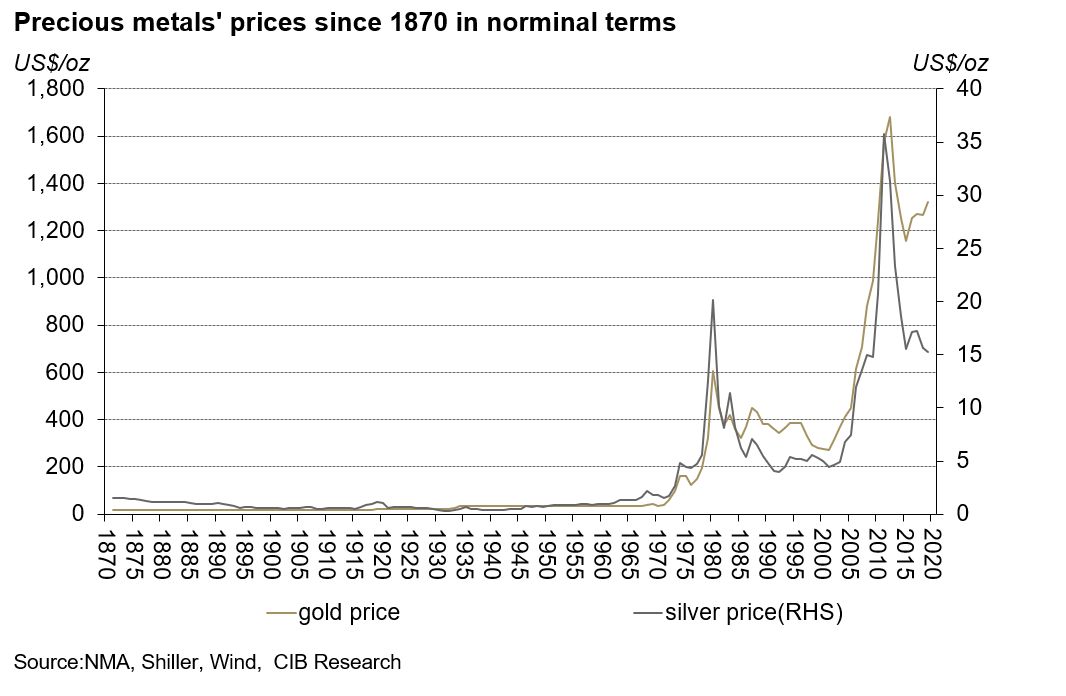

Fast forward almost three decades and, on August 13th 1971, President Nixon decided to terminate the Bretton Woods System, which had formed the basis for global currency markets since the Second World War. In December 1971, the G10 economies signed the Smithsonian Agreement in Washington DC, adjusting the official price of one ounce of gold from US$35 to US$38, implying an instant 7.9% depreciation of the dollar. Between 1971 and 1973, the gold price soared from US$35 to nearly US$100 per ounce.

Both gold bull markets were both directly caused by the revaluation of the gold price during periods of extreme economic weakness, which triggered global currency market crises.

2. Bond Bull Markets

In some respects, gold is a bit like a super-sovereign, zero-coupon bond. It has an intrinsic value, it is highly liquid, carries no risk of default and provides no yield. As such, the returns generated by gold depend on its underlying value rising over time.

Much like bonds, the price rises as yields fall, a trend that was particularly evident during the two big US debt crises of the past 100 years, the Great Depression in 1929 and the Subprime Crisis in 2008.

The US authorities dealt with both crises in a similar fashion: they reduced short-term interest rates to around zero, thereby injecting liquidity into the financial system and depreciating the dollar against major currencies. Gold benefited from this policy on two counts.

First, as gold is priced and traded primarily in dollars, its purchasing power increased as the US currency weakened. Second, as interest rates were cut, bond yields fell in sync. This reduced the opportunity cost of investing in gold, a non-income-bearing asset.

Deleveraging in the Great Depression and the Subprime Crisis

After the 1929 stock market crash, the Federal Reserve (Fed) reduced short-term interest rates to around zero and replaced short-term Treasury bonds with long-term Treasury bonds (known as the twist operation).

The deleveraging process that took place after the subprime crisis was very similar. The Fed reduce short-term interest rates to about zero and adopted the twist operation.

On both occasions, the dollar depreciated against other major currencies and gold. However, this time round, the Fed employed large-scale asset purchases too.

Given the pervasive effect of the US subprime crisis, most developed economy central banks followed the Fed and initiated quantitative easing. In 2015, the European Central Bank went one stage further, introducing negative interest rates, which precipitated a surge in negative-yielding bonds. Since that time, the whole world has entered into an ultra-low or even negative interest rate environment.

This encourages investors to focus on capital gains, rather than yield – a trend that plays to gold’s advantage. Looking ahead, therefore, negative interest rates are likely to provoke further increases in the gold price.

3: Commodity Bull Markets

Gold can also benefit when commodities move into a bull phase.

Commodity prices are closely related to economic cycles. In the 1970s, 1980s and the beginning of this century, for example, mining activity was constrained just as construction activity increased. This created a significant imbalance between supply and demand, and a sharp rise in bulk commodity prices, particularly industrial metals such as copper. Gold also rose on these occasions, partly because it is often included in commodity indices but also because rising commodity prices tend to go hand-in-hand with rising inflation and gold is widely acknowledged as a safe-haven, anti-inflationary asset.

Currency crises, bond bull markets and commodity bull runs rarely occur independently of one another. Indeed, a gold bull market usually arises when more than one paradigm is in evidence. Nonetheless, one tends to be dominant in each bull cycle.

Prospects for gold: a new bull market dominated by the bond paradigm

We believe that bond prices are the dominant force behind the current gold bull market. Bulk commodities are relatively plentiful, so there is little danger of demand outweighing supply and prices are unlikely to show sustainable gains. On the bond front, however, the US is now at the end of its current debt cycle. History shows that deleveraging tends to begin – and economic conditions start to deteriorate - when US corporate leverage rises by 7% to 10% compared to the last cycle. The current upswing began in 2010, leverage has reached a critical stage and a new round of deleveraging seems to be underway.

Back in the days of the Great Depression, a fierce round of deleveraging was followed by monetary tightening, as signs of stability emerged. The change of Fed policy began around 1937. By this stage, however, loose monetary policy had pushed asset prices to a new high. This prompted fears that aggressive tightening could provoke another crisis and a stock market crash. As equities came under pressure, the Federal Reserve began lowering rates again and by April 1938, the short-term interest rate had come down to zero. The stock market then stabilised and started to rebound.

This could be what we are experiencing today. However, it should be noted that the stock market rebound was temporary: despite US rate cuts, the bearish trend lasted until 1942.

There are already signs that US markets are becoming wary of excessive leverage and the Federal Reserve has begun to cut short-term interest rates. Most market observers expect further cuts and some speculate that more quantitative easing is around the corner, Either or both of these would probably provoke another round of dollar depreciation. Gold should benefit further from the low or even negative interest rate environment as well as the depreciation of the dollar, and the bull market will gain fresh momentum.

First, US Treasury yields, which act as a global bond benchmark, are expected to fall, leading to lower bond rates worldwide and a rise in the number of negative-yielding assets. In such an environment, the opportunity cost of investing in gold is largely decreased. Second, the dollar still has a major influence on the gold price. A depreciating dollar enhances the purchasing power of gold and highlights its properties as a stable asset whose value appreciates over time.

There is another angle too: “de-dollarisation", the decision by many countries around the world to purchase fewer dollars and increase their exposure to other currencies and to gold. Highlighting this trend, central bank gold reserves have increased significantly, with China and Russia among the biggest buyers worldwide.

When the global monetary system was restructured in the 1930s and again in 1970s, this incurred a tremendous increase in gold, amounting to 70% and 340% respectively in nominal terms. Dedollarisation may have the same effect.

On every count therefore, gold can be expected to move from strength to strength.