India has a long history of mining gold, but at a low level: 2020 gold mine production was just 1.6 tonnes. Legacy processes are in part to blame: investment in the sector has been discouraged by unwieldy processes.

The government has taken measures to address this through regulatory changes in recent years such as the 2019 National Mineral Policy and early amendments to the longstanding Mines and Minerals Act.

The effects of these measures will not be realised for some time – developing and commissioning a mine is a lengthy process. But, provided that the government’s efforts to streamline the industry are successfully implemented, new policies should eventually stimulate growth. In our view, there exists significant potential to kick start gold mining in India.

Gold mining history

India has a rich heritage of gold mining, albeit on a small scale

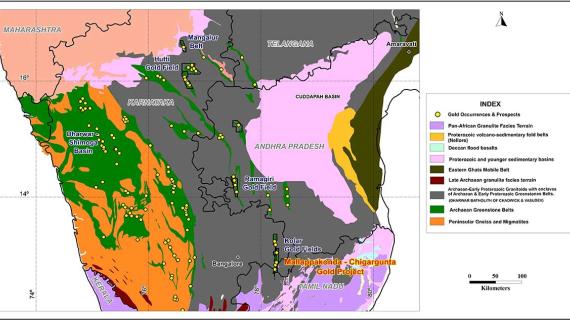

The geology of the Indian Peninsula (South of the Himalayas) is predominantly made up of four Archaean cratons, Proterozoic belts, and sedimentary basins alongside the much younger basalts of the Deccan traps. The Dharwar craton, in the south of India, is the most significant geological formation for gold mineralisation, with lesser occurrences also identified in the other Archaean cratons and Proterozoic units in the country. Gold mining in India dates back to the first millennium BC and throughout the twentieth century was dominated by the Kolar Gold Field, near Bangalore. The field is hosted within the Kolar Greenstone Belt, a 3-6km wide by 80 km long band of greenstone geology – a terrain similar to that which hosts many of the world’s most significant gold discoveries. The Belt predominantly lies along the southeast edge of the state of Karnataka, but also under parts of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu (Figure 1).

The Kolar Gold Field closed in 2001, having produced more than 800t of gold during its 120-year history.1 During its first two decades of operation (1884-1904) the average grade of the ore produced from shallow underground working was an impressive 45g/t, while over its total life span the average ore grade was 15g/t. By comparison, gold grades from South Africa’s prolific Witwatersrand Basin averaged around 9g/t over a similar time frame.2

In subsequent years, gold was primarily extracted from three mines within the East Kolar region: Champion, Mysore and Nundydoorg. By the late 1990s, however, mining had become uneconomic due to reducing grades and increasing costs, and the Kolar operations were finally abandoned in 2001. By this point production had reportedly reached a depth of 3,200m (one of the deepest gold mines in the world), while workings stretched along a 7.3km strike and included 100 shafts and 1,400km of underground development.3

Geological map of Dharwar Craton including the Kolar Greenstone Belt

The other significant gold producer in India has been the Hutti Gold Mine, located in the Raichur district of Karnataka.4 The operation initially entered production in 1902, although it subsequently closed in 1918 because of a paucity of funds due to World War I. Since its restart in 1947, through to 2020, it has produced some 84t of gold and is currently the only significant gold producer in India.

Ore from the main Hutti mine is now supplemented by satellite feeds from the Uti (open pit) and Hira-Buddinni (underground) deposits. Higher grade ore processed at Hutti in 2019 was responsible for boosting India’s gold output by 22% y-o-y to 1.9t; gold reserves are sufficient to support production at the current rate for another 30 years.5

Gold mining production declined marginally to 1.6t in 2020 as the mine closed in April of that year due to Covid-19 (Chart 1).

Historically, gold has also been produced from other deposits, including as a by-product of domestic copper production, although these additional sources have produced limited volumes. The main source of India’s gold from other deposits is Birla Copper’s smelter at Dahej in Gujarat, which processes domestic and imported copper concentrate.6 The plant has an installed gold capacity of 15t per year, although output was below this level in 2020 at 6t.7

Chart 1: Indian gold mine production from primary sources*1970-2020

Indian gold mine production from primary sources*1970-2020

Indian gold mine production from primary sources*1970-2020

* Mine production includes production from primary sources only and does not include output from secondary sources e.g., Birla Copper Smelter, which processes domestic and imported copper concentrate.

Source: Indian Bureau of Mines, Ministry of Mines, Metals Focus

Sources:

Indian Bureau of Mines,

Metals Focus,

Ministry of Mines; Disclaimer

* Mine production includes production from primary sources only and does not include output from secondary sources e.g., Birla Copper Smelter, which processes domestic and imported copper concentrate.

Indian gold mineral reserves and resources

Gold has recently been discovered in a broad range of locations across India, although the majority of economically extracted mineral reserves are located in Karnataka. According to data published by the Ministry of Mines, India’s current defined gold reserves total 70.1t (17.2Mt at 4.1g/t).8

Chart 2: Indian gold reserves and resources are concentrated in Karnataka and Rajasthan

Indian gold reserves and resources are concentrated in Karnataka and Rajasthan

Indian gold reserves and resources are concentrated in Karnataka and Rajasthan

Source: Indian Bureau of Mines, Metals Focus

Sources:

Indian Bureau of Mines,

Metals Focus; Disclaimer

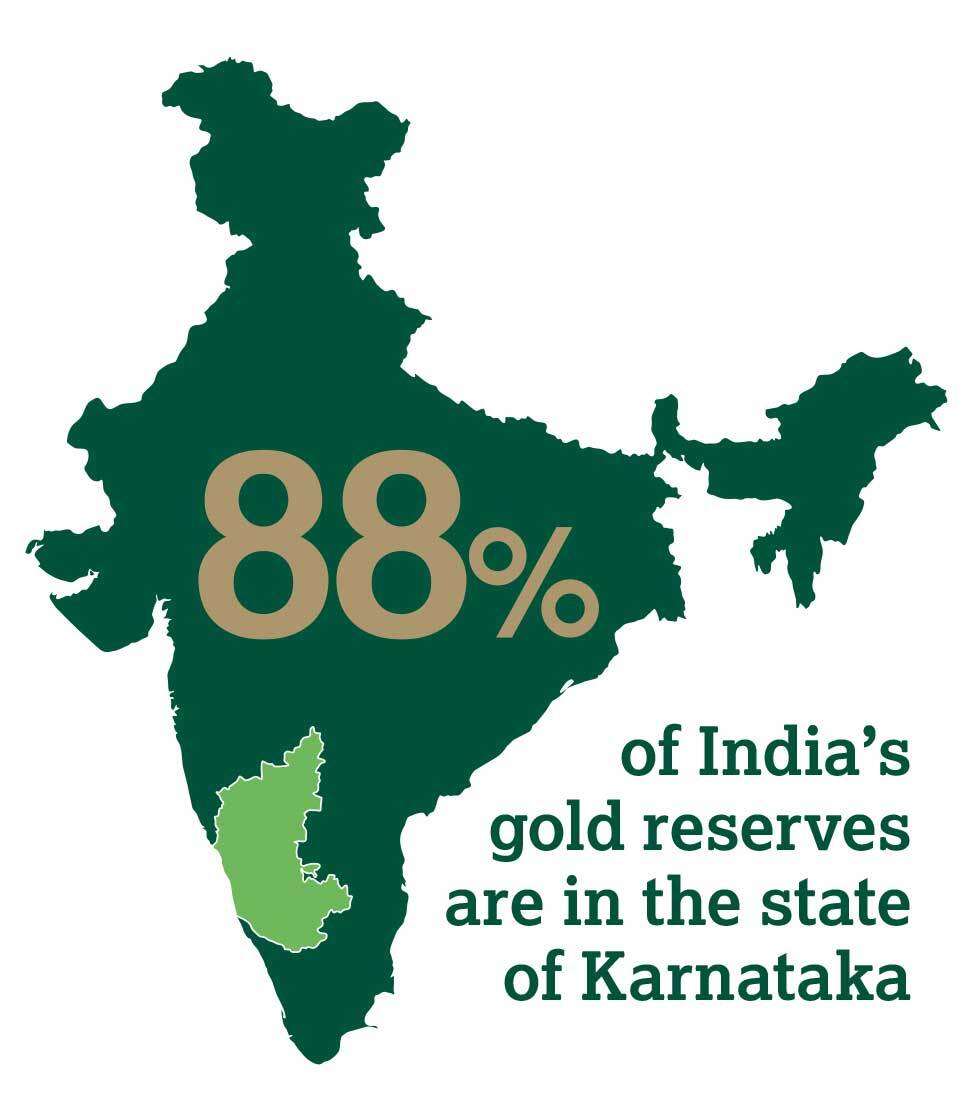

The majority of these reserves are located in the state of Karnataka and account for 88% of the total; a further 12% are situated in Andhra Pradesh and an insignificant amount (less than 0.1t) are found in Jharkhand.

In addition to the aforementioned reserves, 584.7t of gold (484.6Mt at 1.2g/t) is defined in the primary (hard rock) resource category, while 5.9t (26.1Mt at 0.2g/t) has been defined within placer deposits (Chart 2).9 These resources are more geographically diverse, with 47% located in Karnataka, 35% in Rajasthan and 6% each in Andhra Pradesh and Bihar. The remaining 6% is spread across a further eight states.

Future of gold mining in India

India’s gold mining industry has been hampered by onerous legacy processes and under-investment

Until recently there had been no real policy push to promote domestic mining in India, despite it being one of the world’s largest consumers of gold. After legislation was passed in 2003 allowing private organisations to apply for mining leases, a few private and locally-listed companies began operations. But it’s not the market is not an easy one to enter.

Three areas have been problematic in the development of the industry:

Until recently regulatory provisions made it difficult to transfer mining leases or prospecting licences between companies. In addition, prospecting licence holders are not entitled to a preferential claim to a mining lease even if exploration is successful in identifying a viable deposit. This discourages grassroots exploration as even if a deposit is successfully found, the company may not be able to develop it or sell it on.

The process of securing approval for a mining licence is usually lengthy, involving multiple agencies and requiring 10-15 approvals for a single licence. Applications are often subject to substantial delays, leading to lengthy and costly hold-ups in project development. All of this dissuades investment, particularly from multi-national companies who can invest their resources into countries with similar geological perspectivity but with less legacy burden.

The Indian government has reduced taxation on corporate profits over the last few years. However, import tax on mining equipment and other direct and indirect taxes remain high compared to other countries.10 In the absence of domestically-produced alternatives, project developers have little option other than to import specialist mining equipment, much of which comes from a small number of manufacturers. High import taxes increase capital cost and deter development.

Many of the key gold mining areas are in remote locations in states with poorly developed infrastructure. In particular, inadequate road and rail links can make moving materials to and from sites difficult and costly.

As a result, there has been limited investment in gold exploration over the past 15 years, particularly from the private sector. As of March 2018, only 11 gold mining leases were in place across the whole of India.11 In 2019 mining activity was in progress in only four of these permit areas, three of which – Hutti, Uti and Hira-Buddinni – are located in Karnataka and are operated by Hutti Gold Mines. The fourth active mine is Kunderkocha in Jharkhand, and is operated by Manmohan Industries. Production from the Kunderkocha mine is trivial, with output of just 3kg in the financial year 2018-19.

With the right investment and regulatory progress, the industry has potential to grow

There are a couple of nascent projects that should reach fruition in the coming years, particularly if government measures are successful in simplifying onerous processes for the sector.

As these new projects enter production Indian gold output will increase, albeit from a very low base. Deccan Gold Mines had been expecting to bring its flagship Ganajur Main project in Karnataka into production in late 2020.12 However, this project has been delayed several times over recent years and ongoing permitting issues may cause further delays to its start date.13 Output is expected to average 0.9t per year once the mine is operational. Meanwhile, Geomysore Services India has been developing the Jonnagiri project in Andhra Pradesh.14 A mining lease was granted for Jonnagiri in October 2013 and the feasibility study for the project indicates that it will produce an average of 0.7t of gold per year. Geomysore expects to begin production in late 2021 if land acquisition and permitting are completed on schedule. These two projects combined have the capability to double annual mined gold production in India, albeit to a still very modest 4t per year.

Apart from these two projects there is nothing that is likely to increase India’s gold output over the next few years. Over the longer term, a number of deposits have been identified by private companies and the Geological Survey of India, and these may be developed in the future. However, substantial investment would be required to bring these projects to production – something that has been lacking in the sector over recent years. Without such investment, the long-term growth of India’s gold output will remain muted but, streamlined processes and policy certainty should help to encourage investment in gold mining.

The government has recently taken steps towards addressing these challenges

In recent years the Indian government has proposed and implemented various policy changes designed to help develop the gold mining sector by addressing the three most problematic areas outlined above.

In March 2015, parliament approved an amendment to the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act 1957 (MMDR), which allowed private companies to bid for mining leases via a competitive auction process and extended the period for major mining leases from 30 to 50 years.15 Under the auction process, a total of 103 mining blocks were allocated between February 2016 and June 2020, of which four are gold mining deposits.16

In February 2016 London-listed Vedanta Resources became the first private company to successfully bid for a gold mine in India – the Baghmara gold mine in Chhattisgarh – with potential gold reserves of 2.7t of contained metal. Further amendments were also accepted in May 2016, under which captive mining blocks can be transferred without the need for auction.17

In June 2016 the government approved the National Minerals Exploration Policy (NMEP) in an attempt to stimulate mining exploration.18 The policy allows private companies to enter into a transparent bidding process, conducted via e-auction, to carry out exploration of mineral-bearing areas. The company that has won the bid is entitled to a share of royalties paid to the relevant state government. Furthermore, in March 2019 the government announced the implementation of the new National Mineral Policy (NMP 2019) in an attempt to reduce bottlenecks and encourage development in the sector.19 This policy applies to non-coal and non-fuel minerals, and aims to increase the value of minerals produced in India by 200% over a seven-year period.

The salient features of the NMP 2019 are:

- To incentivise exploration through a “Right of First Refusal” when the auction takes place.20 The principal benefits will be a seamless transition between the awarding of the reconnaissance permit through to the prospecting licence and the award of the mining lease. There are also plans to auction combined permits that will cover all of these steps

- A more streamlined permit award method with simple, transparent and accountable processes and clear deadlines, all of which should encourage exploration

- The creation of dedicated mineral corridors to make it more straightforward to transport minerals from mining areas to processing locations

- The granting of ‘industry’ status, which will bring the mining sector better access to banking finance and lower taxes, and should encourage the private sector to become more engaged with financing all aspects of mining, from prospecting and exploration to mine development

- For minerals that cannot be extracted in India, procedures will be introduced to allow public and private entities to acquire mineral assets in other countries

- A long-term import and export policy for minerals will be developed to help the private sector with its long-term planning

- Areas that have been reserved for Public Sector Units (PSUs), but remain unused, will be rationalised and made available to the private sector

- Efforts will be made to align royalties, levies and taxes with overseas mining jurisdictions to help make India a more attractive destination for inward exploration and mining investment.

In May 2020 the Finance Minister, Ms. Nirmala Sitharaman, also announced measures to enhance private investment in the Indian mineral sector as part of the Self-Reliant India Movement,21 including:

- the introduction of a seamless exploration, mining and production regime

- 500 mining blocks that are to be offered through an open and transparent e-auction process

- the abolition of any distinction between captive and non-captive mining blocks, which will allow for the transfer of mining leases.

In January 2021 the cabinet approved proposals for changes to the MMDR 1957, which were broadly in line with the measures announced as a part of Self-Reliant India22 and the Act was approved by parliament in March 2021. The move will help pave the way for a more transparent auction of 500 mining blocks of various minerals, including gold, and will help facilitate a more seamless transfer of leases.

The economic impact of gold mining

Gold mining has the potential to provide significant sustainable socio-economic development for India, not just through investment in exploration of and mining for gold, but also through the legacy of training a skilled workforce. Furthermore, mining helps to bring infrastructure investment to a region, initiating and supporting associated service industries, many of which often persist long beyond the working life of the mine.

Mining can also provide significant employment opportunities to rural areas. Currently, Hutti Gold Mines employs over 4,000 workers and contractors, and it is estimated that each of those workers supports around five dependants.23 Our report, The social and economic impacts of gold mining, showed that 70% of total expenditure by gold producing companies was via payments to local suppliers and contractors, and wages to employees.24 This highlights the important impact even a small gold operation can have on its community.

Given that India is one of the world’s largest gold consuming countries, it makes sense for it to develop mining capacity. But change is needed for this to happen: legacy hurdles must be reduced considerably and investment encouraged. There are promising signs with the changes to the MMDR and the introduction of the NMEP and NMP. If this trend continues India’s mine production is expected to increase. That said, we see this materialising only over the longer-term as potential investors will, for the foreseeable future, wait to see how successfully the new policies are implemented and how effective they will be.

The potential longer-term scale and economic impact of Indian gold production can be estimated by comparisons with other gold producing nations. India’s current resources, when compared to production and resource levels in other countries, could reasonably be expected to support annual output of approximately 20t per year in the longer-term. Should such a level be reached, it would generate almost US$50m in revenue per year for India from royalty payments at current gold prices. Royalty rates from primary gold production in India are set at 4% of the LBMA gold price.25

This would also provide direct employment for an estimated 3,000-4,000 people in addition to those currently employed in the industry. It should be noted that Hutti Gold Mines currently employs a similar number of people, however new mines would be more mechanised and therefore far less labour intensive than current mining at Hutti. To develop a gold mining industry of this magnitude, India would need to attract investment in excess of $1bn to convert resources into reserves and ultimately construct mines.

The current state of the gold mining industry in India and the timescales required to undertake the necessary work to develop mines suggest it would likely take up to 10 years for Indian output to reach these levels. However, an expansion of this magnitude is dependent on legacy hurdles being lifted and India being transformed into an attractive destination for gold mining investment over the next few years.

It is important to remember that the Indian gold mining industry has to compete for investment funding with other gold producing countries. Many of these countries already have a robust and well-established framework to support exploration and mining, and many are equally or more geologically prospective for gold than India. It is only when investors can see real evidence of India managing its gold mining assets more efficiently that we can expect inward investment to emerge. And at that point, the country’s gold mining sector will enjoy a much brighter future.

Contributors

We commissioned Metals Focus, one of the world’s leading precious metals consultancies, to conduct this independent research study with the help of their ‘on the ground’ presence in India. With a team spread across nine countries, Metals Focus is dedicated to providing world-class statistics, analysis and forecasts to the global precious metals market. We are extremely thankful to Chirag Sheth, Adam Webb and Harshal Barot from Metals Focus for their contributions to this report.

Chirag Sheth is a principal consultant with Metals Focus and based in the Mumbai office. Chirag analyses the precious metals market of South Asia, as well as Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam. He has over 13 years’ experience in precious metals trading and research work for UBS and Latin Manharlal Commodities. He is also a visiting faculty to management institutes and features on business news channels in India.

Adam Webb is a director of mine supply with Metals Focus and based in the London office. Adam is responsible for research and analysis of supply and operating costs across gold, silver an the PGMs. Previously, as Head of Mine Economics at S&P Global Market Intelligence, he led supply and costs research across 15 commodities.

Harshal Barot is a senior consultant with Metals Focus, also based in the Mumbai office. He has a decade’s experience as a precious metals analyst and is a regular contributor to Metals Focus work on prices and macroeconomics. Harshal is also jointly responsible for Metals Focus’ precious metals research and analyses other South Asia markets, focusing on Sri Lanka and Nepal.

Footnotes

Geological Survey of India.

South African Chamber of Mines.

Geomysore Services India Private Limited.

The Hutti Gold Mines Company Limited.

Indian gold ore reserves are 17.2 Mt (million tonne) with a grade of 4.1g/t.

Birla Copper is a subsidiary of Hindalco Industries.

Indian Minerals Yearbook 2019 (58th Edition), Part II: Metals & Alloys, Gold - Government of India Ministry of Mines, Indian Bureau of Mines.

Ministry of Mines, Government of India – Annual Report 2019-20.

Placer deposit is an accumulation of valuable minerals formed by gravity separation from a specific source rock during sedimentary processes.

Import tariff data, World Trade Organisation .

Ministry of Mines, Government of India – Annual Report 2019-20.

Deccan Gold Mines.

Deccan Gold Mines Hearing before the High Court of Karnataka on 2 March 2021.

Geomysore Services India.

The Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Amendment Act, 2015.

Ministry of Mines, Successful Auction Details.

The Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Amendment Act, 2016. A mining block is an area for which the government has granted permission in the form of a mining licence to mine minerals. A captive mining block is used to meet the needs of the block owner, or of the parent company, subsidiary or affiliates of the mine owner and the output from the mining block is not intended for open market sale.

National Mineral Exploration Policy 2016, Government of India.

National Mineral Policy 2019, Government of India.

Right of First Refusal is a contractual right that gives its holder the option to enter a business transaction with the owner of something, according to specified terms, before the owner is entitled to enter into a business transaction with a third party.

Press Information Bureau.

Bloomberg Quint.

The Hutti Gold Mines Company Limited.

Please refer to the latest version of the report, The social and economic contribution to gold mining published in 2021.

Ministry of Mines, Government of India – Annual Report 2019-20.