While gold’s contribution to managing portfolio risk is well established, supported by a large body of work devoted to its hedging characteristics,1 its contribution to portfolio return is not. Frameworks for estimating gold’s long-term return exist but fall short of a robust approach that aligns with the capital market assumptions for other asset classes. This report sets out such a framework, accounting for gold’s unique dual nature as a real good and a financial asset.

Publications tackling gold’s expected return have generally concluded that gold’s primary function is as a store of value, implying a long-run co-movement of gold with the general price level (CPI). Alternative approaches using risk premia estimations or bond-like structures with embedded options produce similar results.

And while existing research is rich in insight, two features frequently pop up that, in our view, mischaracterise gold and have led to biased conclusions:

- Using data from periods during the Gold Standard to analyse gold’s performance paints a misleading relationship between gold and general prices2

- Viewing long-term price dynamics exclusively through the lens of demand from financial markets and ignoring other sources of demand, is a likely contributor to a systematic underweighting of gold in private portfolio allocations.

In most cases, these theories land on an expected long-run real return ranging between 0% and 1%.3

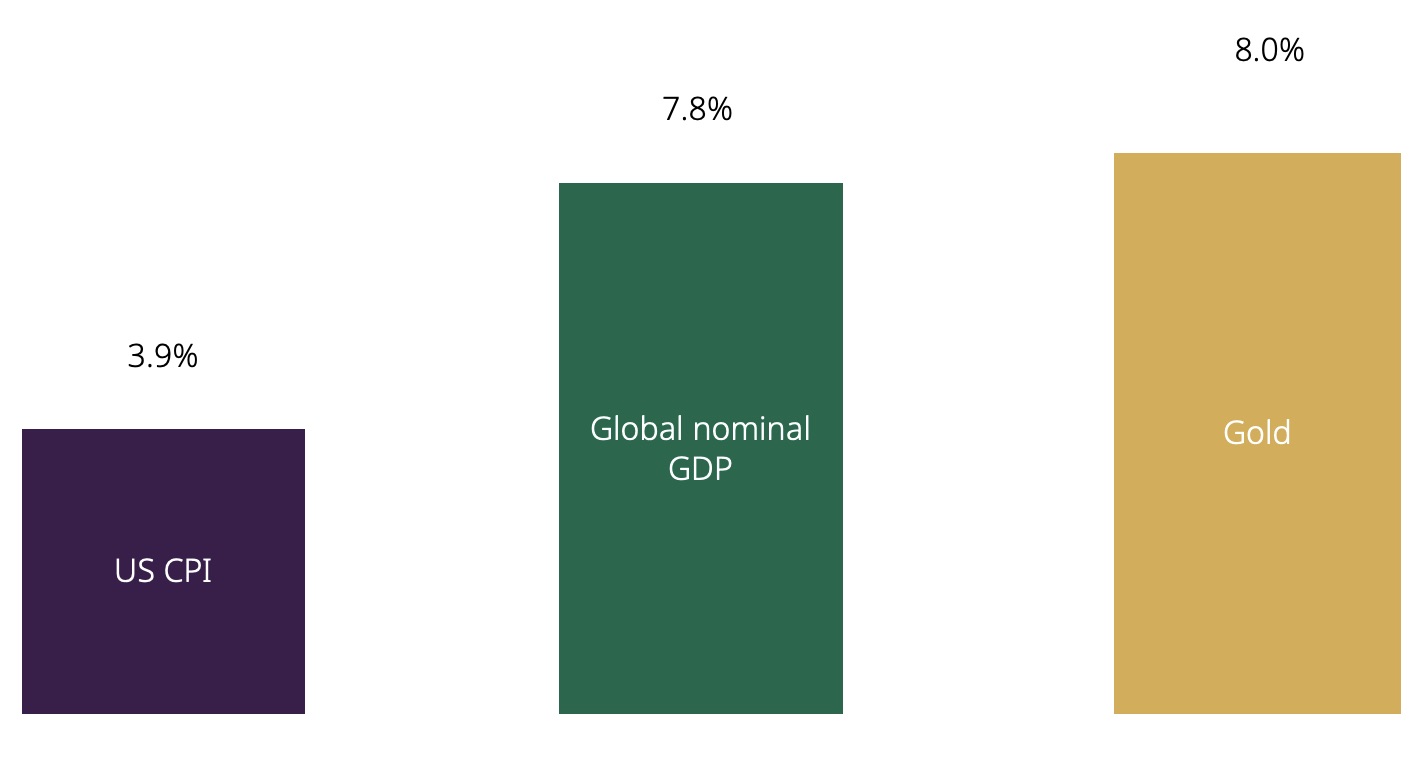

We instead show that gold’s long-run return has been well above inflation for over 50 years (Figure 1), more closely mirroring global gross domestic product (GDP), a proxy for the economic expansion driver used in our other gold pricing models.

Our simple yet robust approach – which we refer to as Gold Long-Term Expected Return or GLTER – uses the distribution of above-ground gold stocks analysed via different demand categories as a foundation and starting point.

The drivers of gold buyers across various demand segments – jewellery and technology fabrication, central banks, financial investment, retail bars and coins4 – are crucially broader and more important than existing theories suggest.5 In addition, although financial market investors tend to dictate price formation in the short term, they are less dominant in the long term.6

We show that the gold price over long horizons is mainly driven by an economic component, proxied by global nominal GDP, coupled with a financial component, proxied by the capitalisation of global stock and bond markets, that balances the overall relationship. Third-party inputs are then used to estimate long-term expected returns for gold.7

Figure 1: Gold’s return over the past 50 years has been in line with global GDP and well above inflation

Annual growth in US CPI, global nominal GDP and gold price (1971–2023)

Footnotes

1. For a discussion of this research see O’Connor (2015)

2. Prior to the closure of the gold window, gold was primarily a monetary asset that could only be bought and sold at its official price in most jurisdictions.

3. The most commonly applied deflator to achieve real returns is the US consumer price index.

4. Defined as purchases of bars and coins less than 1kg in a retail setting. See Supply and Demand notes and definitions.

5. Further details of the data can be found here.

6. In reality the delineation between short term and long term isn’t easily done, suffice to say that supply chain buffers delay transmission to price from some demand sectors such as jewellery, retail bar and coin and technology.

7. This report does not purport to forecast the gold price or future performance of gold. This report sets out a proposed methodology and highlights the expected long-term returns for gold utilising third-party input assumptions. The World Gold Council does not make any recommendation or suggestion as to appropriateness of particular inputs into the model. Users can apply different inputs, which will generate different long-term expected returns for gold.