We proxy the economic and financial components using real-world economic and financial variables. Our economic component proxy is global nominal GDP in US dollars. Nominal GDP comprises real GDP, an inflation component (the GDP deflator) and a currency component – used to convert local GDP to US dollars. This captures the flow of capital from income to gold.

Our financial component is proxied using the capitalisation of global equity and bond markets – the global portfolio – in US dollars. It captures the investments available for investors to reallocate income and wealth. It is important to note that we are looking at market capitalisation, accounting for both quantity of float and issuance, not just prices.1

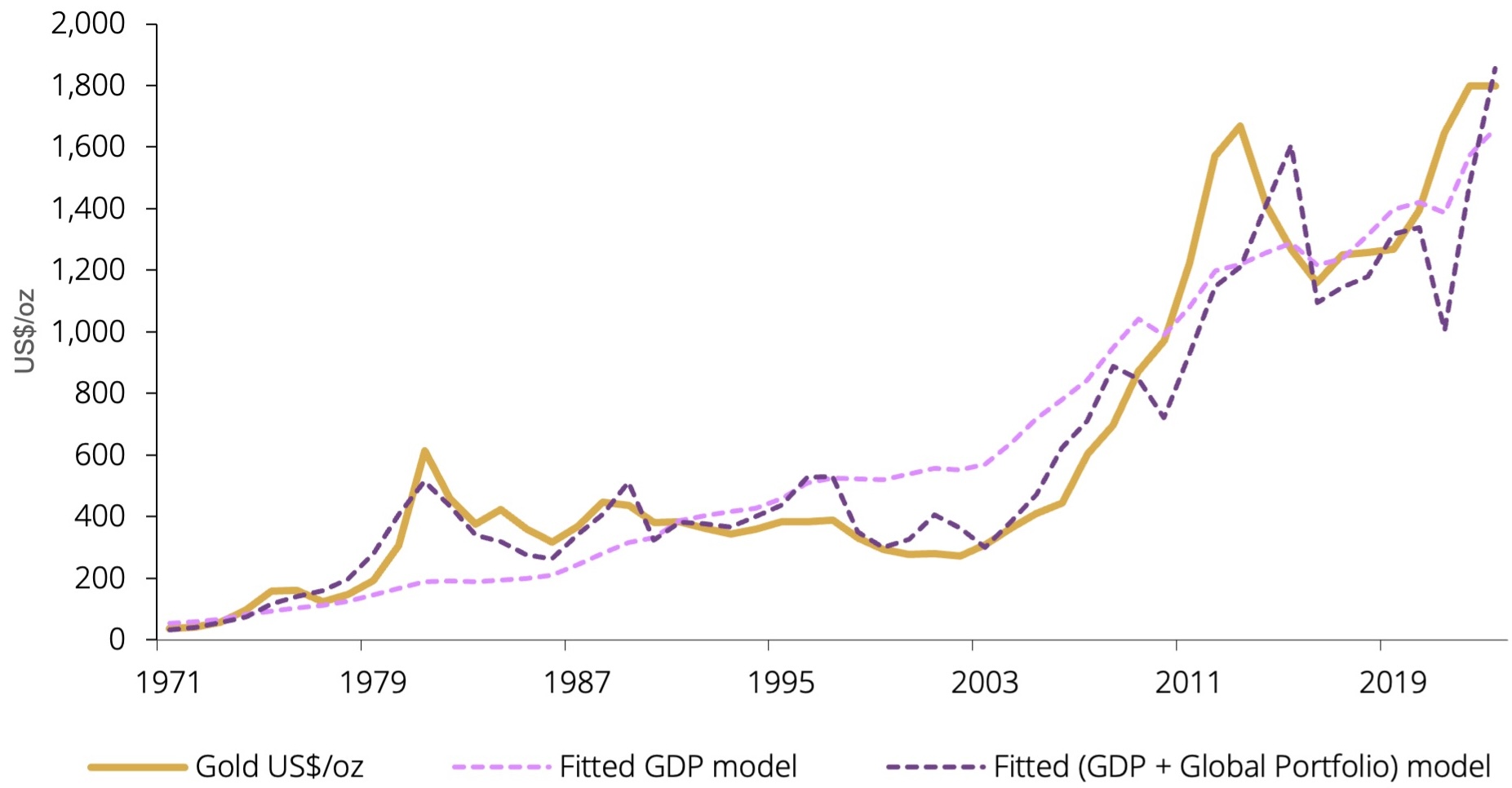

We assess the influence of each of these variables using regression analysis. The analysis reveals that GDP is the primary driver of the gold price in the long run.